We used to treat PCBs as simple component holders. But as we push designs into the GHz or mmWave ranges, the board’s substrate stops being a passive stand. It becomes an active participant in the circuit. High-frequency PCBs introduce challenges like dielectric loss, impedance drift, and signal integrity issues that simply don’t exist at lower speeds. At these frequencies, you aren’t just managing connections anymore; you’re managing physics.

The substrate directly influences signal speed, loss, and impedance. Choose the wrong material, and you invite excessive signal loss or impedance mismatches that drift with temperature. But get it right, and the substrate supports high-frequency performance so seamlessly you forget it’s there. We’ll look at why the material you choose is the single biggest factor in the success of these designs.

Key Takeaways

- High-frequency PCBs rely heavily on substrate material, as it significantly impacts signal integrity, dielectric loss, and impedance stability.

- Using standard materials like FR-4 can result in increased signal loss and inconsistencies, particularly at GHz ranges; specialized laminates offer better performance.

- Key properties for high-frequency PCBs include Dk stability, low loss tangent, moisture resistance, and thermal stability.

- Designers should match material properties to frequency, trace length, environmental conditions, and application to ensure optimal performance.

- Partnering with a specialized manufacturer simplifies the fabrication of high-frequency PCBs, allowing for expert input and reliable production.

Table of Contents

- Why Material Choice Is Critical for High-Frequency PCBs

- Critical Material Properties for High-Frequency PCBs Performance

- Why Dk Stability Wins

- Managing Signal Loss

- Moisture: The Silent Signal Killer

- Handling Temperature Shifts

- Mechanical Traits and Processing

- Matching Materials to Your Signals and Environment

- Partnering with an Expert Manufacturer

Why Material Choice Is Critical for High-Frequency PCBs

High-frequency circuits, whether in 5G base stations, radar systems, or high-speed digital interfaces, are unforgiving. At these speeds, your PCB material isn’t just a canvas for components; it is a component. Even minor characteristics can make or break performance.

We can pin this volatility down to three main factors.

1. The Hidden Costs of FR-4

We all rely on FR-4 for standard boards. It’s cheap, available, and usually gets the job done. But ask it to handle gigahertz frequencies, and it shows its limits. As frequency rises, FR-4’s dielectric constant becomes unstable, and its loss tangent, the measure of signal lost as heat, spikes.

John Coonrod from Rogers Corporation puts this in perspective: typical FR-4 has a dissipation factor around 0.020. An engineered high-frequency PCB laminate sits around 0.004. That’s roughly one-fourth of the loss. For your design, this difference often decides whether your wireless link budget holds up or fails to meet timing.

2. Chasing Impedance Stability

Then there is the fight for consistent impedance. Signal integrity demands precise impedance, usually the industry-standard 50 Ω. FR-4 introduces a wildcard. Its dielectric constant (Dk) is rarely static, often shifting by 10% or more between production lots.

A 50 Ω design on your screen can easily become a 45 Ω or 55 Ω reality on the test bench. That mismatch causes reflections and ringing. Specialized substrates, such as PTFE laminates, hold a much tighter Dk tolerance, often within 2%. You get the stability you designed for, ensuring your signals propagate cleanly rather than getting muddled by the board itself.

3. When Insulators Act Like Resistors

Finally, we have to look at what happens when you push power and speed to the edge. Standard materials can suffer dielectric breakdown when subjected to high RF power or fast switching. We’ve seen cases where an FR-4 board works perfectly at lower speeds but starts leaking signal or heating up at GHz frequencies. The material effectively quits its job as an insulator and begins acting like a resistor. This failure mode drives most serious RF engineers to abandon standard FR-4 completely in favour of specialized high-frequency laminates.

Critical Material Properties for High-Frequency PCBs Performance

Scanning a laminate database can be overwhelming. But if you are building for RF, mmWave, or high-speed digital, you can ignore most of the generic parameters. Focus on the few properties that actually dictate signal integrity.

Why Dk Stability Wins

Also called relative permittivity, Dk dictates how fast signals travel through the board. But for high-frequency work, the raw number matters less than its consistency. You need a material that stays rock-steady across frequency and temperature.

High-frequency laminates typically hold a Dk tolerance of ±2% or better. Contrast that with FR-4, where the Dk often wanders by ±10%. Take a PTFE-based material: it might maintain a Dk of 2.2 within a tiny ±0.02 margin across a wide frequency range. Your impedance stays true across the entire panel. A 10 cm trace on the left side behaves exactly like its twin on the right.

Managing Signal Loss

This is your “lossiness” metric, often called loss tangent (tan δ). A higher Df means more of your RF energy turns into heat as it travels. For high-frequency designs, keeping Df low is the only way to minimize attenuation.

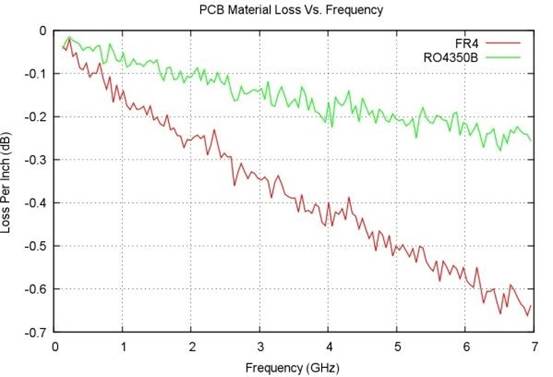

Standard FR-4 typically sits around a Df of 0.02 at microwave frequencies. Specialized RF laminates drop that number to the 0.002–0.005 range. Do the math: a Df of 0.002 cuts signal loss to just one-tenth of what you get with FR-4.

The graph below proves it. Look at the gap between the materials:

You can see the FR-4 (red line) giving up as frequency climbs. At 5 GHz, a trace on FR-4 sheds half its power over just a few inches, while the low-Df laminate retains most of it. Knowing your Df helps you predict if your 10 cm RF trace will act as a crisp transmission line or a bad attenuator.

Moisture: The Silent Signal Killer

We tend to ignore humidity until it ruins a field unit. But water is a high-loss dielectric. Since it has a high dielectric constant, even a tiny amount absorbed into the weave ruins performance by raising the board’s effective Dk and Df.

Traditional FR-4 is notoriously thirsty. Under extreme exposure, it can absorb significant amounts of water. By contrast, PTFE-based high-frequency materials are practically hydrophobic, with absorption figures often below 0.02%. Low moisture absorption means your board won’t suddenly drift out of spec just because it’s deployed in a humid environment.

Handling Temperature Shifts

Your design likely needs to work outside the lab. Whether it’s an automotive radar in a hot engine bay or an aerospace system at high altitude, temperature swings are inevitable. The temperature coefficient of Dk (TCDk) measures how much the material’s electrical properties shift with heat.

FR-4 can shift by around 200 ppm/°C, leading to noticeable drift in circuit behavior. High-frequency laminates are engineered to stay put, often keeping TCDk around 50 ppm/°C or less. This means a filter or antenna tuned at 25°C won’t detune when the device hits -40°C or +85°C.

Mechanical Traits and Processing

Electrical specs aren’t the whole story. Reliability hinges on mechanical traits like the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE). This is crucial for hybrid stacks. Bond a low-loss RF layer to an FR-4 backer without matching CTEs, and the physical stress will eventually crack your vias or warp the board.

Also, watch out for processing quirks. Some high-frequency PCBs substrates, like pure PTFE, are softer or more brittle than standard epoxy glass. They can be a nightmare to drill or plate if the fab house isn’t prepared. We’ll cover manufacturing specifics later, but it’s worth checking now if a candidate material plays nice with standard PCB processes.

Matching Materials to Your Signals and Environment

You don’t always need the most expensive, highest-spec laminate on the market. Over-engineering destroys budgets just as fast as under-engineering destroys performance. The goal is to match the material properties to your specific signal requirements and where the board will actually live.

Here is how we narrow down the list.

1. Let Frequency Dictate the Tier

Start with your fastest signal. Standard FR-4 is perfectly fine for 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi or basic digital boards. But once you cross the 2–5 GHz threshold, FR-4 becomes a liability. It acts like a brake, killing your signal with excessive loss and impedance drift.

The general rule of thumb:

- Sub-5 GHz: Standard FR-4 or mid-Tg epoxy often works.

- 5 GHz to 30 GHz: You need dedicated RF laminates. Rogers RO4350B (Dk ~3.66) is a workhorse here, widely used for 5G base stations and microwave links.

- mmWave (60 GHz+): For 77 GHz automotive radar, the industry leans heavily on materials like Rogers RT/duroid 5880. With attenuation below 0.2 dB/cm, these laminates let the signal pass through with almost zero resistance.

Pro tip: Don’t redline your specs. If your signal hits 10 GHz, don’t buy a material rated exactly “up to 10 GHz.” Buy the next tier up to guarantee stability.

2. Factor in Trace Length

- Distance kills high-frequency signals. If your RF signal only travels 1 cm from a chip to a connector, you might get away with a lossier, cheaper material. But if you are routing long feed networks or array antennas, cumulative loss becomes your enemy.

- Calculate a rough loss budget. Say you have a 10 cm run and can only tolerate 1 dB of loss. Standard FR-4 burns through 0.5–0.7 dB per inch, failing you almost immediately. Switch to a low-loss PTFE laminate (~0.1 dB per inch), and you stay safely within spec.

3. Will It Survive the Environment?

Lab benches are safe; the real world is not.

- Temperature Extremes: Aerospace and automotive rigs endure harsh thermal cycling. This calls for ceramic-filled PTFE. While other materials drift, this stuff holds its specs tight from -50°C all the way to +150°C.

- Moisture: Outdoor gear faces constant dampness. Standard FR-4 acts like a sponge here, soaking up water and shifting your Dk. You need a hydrophobic material, like hydrocarbon ceramic, to stop the environment from detuning your circuit.

- Heat Dissipation: High-power amps get hot, fast. To keep the board from warping or delaminating, you need a laminate with high thermal conductivity to channel that heat out of the system.

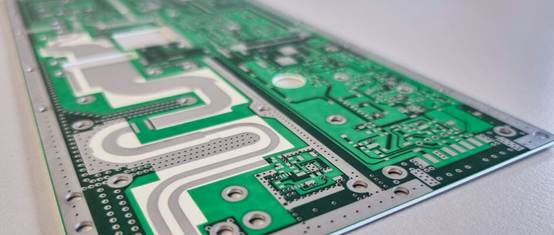

4. Hybrid Stacks: The Budget Saver

Using a $500 laminate for a digital control circuit is a waste. Many designers opt for a hybrid stack-up. Put the expensive, high-performance RF material only on the top layer for your critical signals. Let cheaper FR-4 handle the core and bottom layers for power and digital logic.

A word of caution: Physics doesn’t negotiate. When you bond PTFE to FR-4, their expansion rates (CTE) must match. Mismatch them, and the board will bow or delaminate during reflow. Always talk to your high-frequency PCBs fabricator early to see which hybrid combinations they have qualified.

5. Compliance Check

- Flammability: Check if your project mandates a UL94-V0 rating. Be careful, some pure PTFE materials burn and aren’t V0 rated unless they have specific fillers.

- Standards: Military and aerospace projects often mandate IPC Class 3 or MIL-spec materials. Verify that your chosen laminate is actually listed for the specific standards in your contract.

Partnering with an Expert Manufacturer

Because high-frequency PCB fabrication is unforgiving, you can’t just send files to a random shop and hope for the best. You need a partner with proven RF experience. A specialized provider like Jarnistech brings the right arsenal, from laser direct imaging for fine features to controlled-depth routers for precise cutting. This specific process know-how ensures you get the board right on the first try, rather than dealing with a scrap pile of expensive laminates.

Working with experts also opens the door to early consultation. A quick chat about your stack-up can reveal practical tweaks, like swapping to a stocked core thickness, that smooth out production. A skilled high frequency PCB manufacturer won’t just take your order; they will guide your choices.

Finally, the right partner anticipates challenges before they become defects. They know that ceramic-filled laminates chew through drill bits, so they plan more frequent tool changes to keep hole quality pristine. They also tune their plasma desmear settings specifically to avoid smear on sensitive PTFE. In short, they fix manufacturing problems before they happen, ensuring your advanced design performs exactly as intended in the real world.