In modern digital businesses, reliability is rarely discussed until it fails. Customers expect payments to work seamlessly across regions, devices, and network conditions that are inherently unpredictable. Leadership teams assume continuity. Engineering teams assume correctness. And yet, payment failures remain one of the most damaging and least visible risks in digital operations. A reliable payment system must function predictably even when the surrounding environment does not.

This disconnect exists because payment systems are often treated as technical implementations rather than strategic infrastructure.

Reliable payment systems are not defined by how efficiently they process transactions under ideal conditions. They are defined by how predictably they behave when conditions are uncertain, delayed, or partially failing. That distinction matters far more at scale than raw performance metrics.

Table of contents

- Payments Are Distributed Systems, Not Simple Interactions

- Reliability Starts with Explicit State Modeling

- Idempotency as a Leadership Decision, not a Technical Detail

- Designing for Ambiguity Instead of Forcing Certainty

- Separating Signals from Decisions

- Why Crypto-Based Payment Systems Attract Architectural Interest

- Reliability as an Organizational Capability for a Reliable Payment System

Payments Are Distributed Systems, Not Simple Interactions

One of the most persistent architectural misconceptions is treating payments as synchronous request–response operations. A client submits a payment, receives a response, and the business moves forward. This mental model assumes immediate finality and ordered signals.

Real payment systems do not work that way.

Payments traverse multiple layers: client applications, backend services, external networks, confirmation mechanisms, and asynchronous callbacks. A transaction may be broadcast successfully but confirmed later. A confirmation signal may arrive out of order or be duplicated. Network congestion may delay settlement without indicating failure.

When systems are designed around synchronous assumptions, teams are forced to guess outcomes. Guessing introduces operational risk: incorrect state transitions, double processing, premature failure handling, and reconciliation chaos that surfaces only after scale is reached.

Reliability Starts with Explicit State Modeling

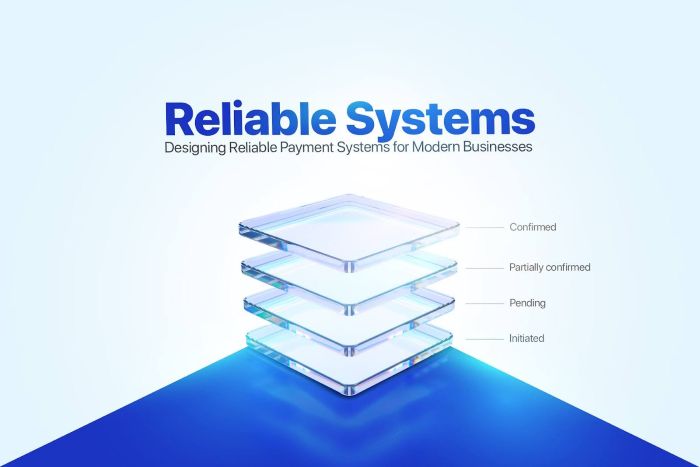

Organizations that build reliable payment infrastructure approach payments as stateful processes rather than binary events. Instead of collapsing outcomes into paid or unpaid, they define explicit, observable states such as initiated, pending, partially confirmed, confirmed, expired, or failed. A reliable payment system depends on explicit state definitions to prevent ambiguity from turning into financial risk.

Each state represents a verifiable condition, not an inference. Transitions between states are deterministic and idempotent. If the same signal is processed multiple times, the system converges to the same outcome. If signals arrive out of order, the system reconciles rather than rejects them.

This approach aligns payment architecture with the realities of distributed systems. It accepts uncertainty as a constraint rather than an exception and designs reliability into the system instead of layering it on through manual intervention.

Idempotency as a Leadership Decision, not a Technical Detail

In production environments, retries are inevitable. Clients retry. Workers retry. External services resend callbacks. Without strict idempotency guarantees, retries quickly become financial risk.

Reliable organizations treat idempotency as a first-class design principle, not a backend optimization. Every operation that can be retried must be safe to replay. This shifts complexity away from ad-hoc error handling and into explicit state modeling where it can be reasoned about, audited, and trusted.

From a leadership perspective, idempotency is about predictability. It reduces operational surprises and limits the blast radius of partial failures.

Designing for Ambiguity Instead of Forcing Certainty

Another common failure pattern is equating silence with failure. In payment systems, lack of confirmation is not a conclusion. It is ambiguity.

Reliable systems recognize ambiguity as a valid state. Instead of timing out and failing transactions prematurely, they remain pending until sufficient evidence exists to transition safely. This reduces false negatives and prevents legitimate payments from being discarded.

Ambiguity-aware design requires discipline. It requires leaders to resist pressure for immediate answers when the system cannot yet provide reliable ones. In return, it delivers fewer disputes, fewer manual corrections, and greater trust in automated workflows.

Separating Signals from Decisions

Signals are inputs. Decisions are outcomes.

In fragile systems, these concepts are often conflated. A webhook arrival is treated as final confirmation. A network response is assumed to represent settlement. When those assumptions fail, systems have no recovery path.

Reliable payment architectures separate signal ingestion from decision logic. Signals are collected, validated, correlated, and evaluated against predefined rules before any state transition occurs. Without this separation, a reliable payment system cannot maintain consistency at scale.

It also improves accountability. Decisions can be traced back to the signals that informed them, making failures easier to analyze and systems easier to govern.

Why Crypto-Based Payment Systems Attract Architectural Interest

Crypto-based payment infrastructure has gained attention not as a trend, but as an architectural response to long-standing limitations in traditional payment rails. When implemented pragmatically, these systems expose explicit settlement rules, observable confirmation layers, and deterministic state transitions.

Rather than relying on opaque intermediaries, modern crypto payment systems expose transaction lifecycles directly to applications. This transparency aligns naturally with state-machine-based design, idempotent processing, and signal-driven workflows.

A practical overview of this approach can be found in this guide on crypto payment system architecture, which illustrates how confirmation logic, settlement states, and automation can be modeled explicitly rather than inferred.

The value here is structural, not ideological. These systems behave the way distributed systems are expected to behave.

Reliability as an Organizational Capability for a Reliable Payment System

Reliable payment systems are not built through dashboards or feature checklists. They emerge from consistent engineering discipline and clear organizational priorities: explicit state modeling, tolerance for ambiguity, idempotent operations, and separation between signals and decisions.

Organizations that adopt these principles build systems that degrade gracefully instead of failing catastrophically. They reduce manual intervention. They improve trust between engineering, finance, and operations teams.

In modern digital businesses, payment reliability is not a backend concern. It is core infrastructure. Ultimately, a reliable payment system reflects an organization’s commitment to predictability, resilience, and long-term operational trust. Systems that acknowledge uncertainty tend to survive it. Systems that assume certainty rarely do.